This interview appeared in a Girls’ Anime special in Animation Note no. 11, published in September 2008, before Michiko and Hatchin started airing in October of that year. The interview has been translated by Twitter user @karice67 Scans were generously provided by Twitter user @zcqxldl © 2017 Wave Motion Cannon

Help fund (and suggest) future translations! Support us on Patreon!

Thank you also to @ten3_1 for helping me confirm it was the one I was looking for. –karice

Sayo Yamamoto

Born in 1977, hails from Tokyo. After graduating from one of the city’s colleges of fine arts, she spent a few years at Madhouse before becoming a freelance director (unit). She’s worked on series such as Samurai Champloo and Ergo Proxy. Michiko and Hatchin is her debut as a series director.

Born in 1977, hails from Tokyo. After graduating from one of the city’s colleges of fine arts, she spent a few years at Madhouse before becoming a freelance director (unit). She’s worked on series such as Samurai Champloo and Ergo Proxy. Michiko and Hatchin is her debut as a series director.

“That would not have been possible if I hadn’t gone location scouting.”

—I’ve heard that, in order to capture the atmosphere of South America on the screen, you did some intensive location scouting.

Yamamoto: Though there wasn’t much time, I think I covered quite a lot of ground. I was even able to go to a favela and other dangerous areas that Japanese travelers typically don’t venture into.

—The film City of God was set in a favela—a slum—in Rio, wasn’t it? I’m amazed that you went to such a dangerous place.

Yamamoto: If I’d seen that film beforehand, I probably wouldn’t have gone. I’d probably have said “I’m sorry, I don’t really feel like going…” (chuckles)

—What is the ‘city of god’ like?

Yamamoto: I thought that it would be inhabited only by gangs and incredibly poor people, but many average, working people also live there. They also have post offices and banks, and many people have computers in their homes.

—Did you run into any dangerous situations while you were there?

Yamamoto: I went on a tour put together by people of the favela, who restricted it to particular areas, so I didn’t encounter anything particularly dangerous. However, the patrol car that had parked itself by the entrance to the area had perfectly formed bullet holes in its windscreen (chuckles).

—That would give you pause, wouldn’t it? (chuckles) Though on this topic, in which episodes does your experience touring the favela make itself felt?

Yamamoto: In the 3rd and 4th episodes. I don’t think stories in those episodes would have been possible if I hadn’t actually gone to a favela.

—I see. But why did you think of making a show with South America as a motif?

Yamamoto: The impetus behind that choice actually came from my trip to Mexico, in Central America, four years ago. I stayed in Mexico City for a while, and it was quite an unsettling experience, wherever I went. There would be middle-aged men, drugged up with cocaine, scattered on the steps of the subways, and groups akin to Japanese biker gangs on the streets (chuckles). And I thought to myself that I’d like to make this kind of scenery—which Japanese people would never have seen—the backdrop for a story. That’s how I started coming up with the idea for Michiko and Hatchin.

“I’ve never seen a single film by David Lynch.”

—Out of all the countries in South America, is there a reason you chose Brazil?

Yamamoto: This is just my own personal opinion, but compared to Mexico and Argentina, it’s a pretty modern and cheery place. You could also see the influence of the architect, Oscar Niemeyer, in public buildings, so it all seems rather stylish.[1] It was all so different from everything I’d seen up until that point. Like the entire town just flows—it’s really interesting.

—And all of that, those sights and sounds you actually experienced, they all seeped steadily into this show as well?

Yamamoto: You could say that. Details such as the bits of graffiti on the walls, or the design of the rubbish bins—I’ve done my absolute best to have that all reflected on the screen. In the end, if you don’t layer all of these minute details on top of each other, I don’t think you’d be able to build your world up successfully.

—I’d also like to ask you about your directorial style. The way you do it, it feels like your episodes cover so much ground that it simply wouldn’t fit into the length of a normal anime episode. You could say it’s…tricky…or perhaps, that the rhythm is kind of unpleasant.

Yamamoto: Is it unpleasant? My directorial style?

—In a good way, I mean. Like, even though you know what kind of rhythm would be pleasing to people watching, you purposefully make it a bit off-kilter. I’m really interested in finding out what the roots of this style are. To me, personally, if feels like you might be influenced by people like David Lynch, or David Cronenberg.[2]

Yamamoto: I’m often told that it reminds people of David Lynch. But the truth is, I haven’t actually sat down to watch one of his films properly.

—You don’t often watch films?

Yamamoto: No no, I do.

—Do you have a favourite film?

Yamamoto: That’s a difficult question. But the film that made me want to work on anime was Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day.[3]

—So your roots lie in Edward Yang? That’s rather unexpected.

Yamamoto: There isn’t a hint of his style in my work, is there? (chuckles) But when I watched that film, I felt that I just wanted to enter into that world. Even today, that feeling remains one of the driving forces behind my desire to create anime.

“I place great importance on the ‘rawness’ of women.”

—Moving on a little, this is just my own wild idea, but when you were young, did you hate characters like (Doraemon’s) Shizuka-chan?

Yamamoto: I did indeed. I just couldn’t understand what was so good about Shizuka-chan and Minami-chan (from Mitsuru Adachi’s Touch) (laughs).

—What did you not like about them?

Yamamoto: The fact that they were conveniently there for their guys. Even as a child, I just went “That kind of gal…just doesn’t exist!” I also didn’t like how they don’t seem to have any individuality. Well, ultimately, that’s how I thought when I was a kid.

—So you think differently now?

Yamamoto: I do. If one of your neighbours were a girl like Minami-chan, and she told you every single day “Do your best! I’m cheering for you!”, wouldn’t you feel like you could do just about anything?

—That wouldn’t be so bad, would it? (chuckles) But it sounds like you are a little frustrated with female characters like that. Is that frustration reflected in the show?

Yamamoto: Quite a bit, in the personalities of the characters and the actions they take.

—In what way?

Yamamoto: Like, there are strong and determined female characters who live by preying off men, characters that I think would put off any guy who watches the show… my tastes are all coming out, aren’t they? (chuckles) In terms of design, then Michiko’s chest, the way it’s like she’s bra-less. Though not what you typically see in anime, that is, symbolic breasts that are like butts; rather, they hang quite naturally…

—I see. But if you keep saying “Like she’s bra-less, like she’s bra-less,” then I suspect that the staff would be rolling their eyes at you.

Yamamoto: It is kind of unpleasant, isn’t it? (chuckles).

“If you don’t think deeply about what you want to do, then what you make won’t become something that is interesting.”

—Finally, do you have any words of advice for readers who are aiming to work in the industry?

Yamamoto: Any advice? Well…travel, fall in love to the point that it might cost you your life—just have lots and lots of different experiences. After all, books and films are all worlds that have passed through the filters of other people, so I think that experiencing and feeling for yourself is really important if you want to become a creator. And you should also ask yourself what it is you want to express in animated form.

—In your case, what is it that you want to express that makes you create anime?

Yamamoto: Right now, it’s women. Their idiocy, the vague relationships between them that aren’t quite friendship or romantic love… I’m making anime because I want to depict these facets of women that I’ve personally felt. I suspect that the highlights of Michiko & Hatchin will come from this focus as well.

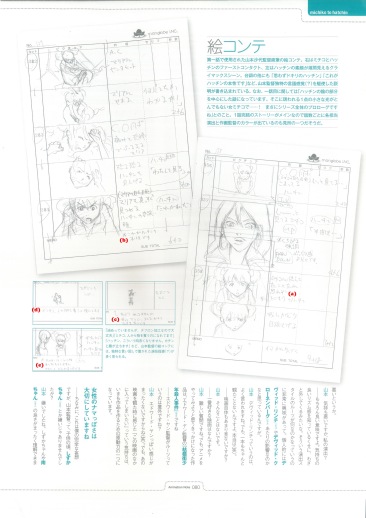

Here (the page to the right) are some of Director Sayo Yamamoto’s storyboards for episode 1. On the right is the scene Michiko and Hatchin meet for the first time, and on the left a climax scene where we catch a glimpse of Hatchin’s true face. Besides the lines of dialogue, there are the director’s characteristic, intuitive (?) explanations, such as (a) “Hatchin instinctively flinches” and (b) “This is Hatchin’s true character.” Furthermore, she has this to say about the first episode: “This is an episode that focuses on the darkness of Hatchin’s life. And the spark of light that appears in it is the outrageous Michiko…! It’s the prologue to the entire series alright!” Most of the episodes will be built around a single story, so the varied colors that the changing episode and animation directors bring will apparently be another of the show’s talking points.

(c) “She hasn’t poured any oil on the pan, but it’s fine because it’s made of Teflon” (04:20) (d) “Michiko is used to stealing from people” (01:15) and (e) “Hatchin doesn’t blush in situations like this, she just gets angry” (05:25): Director Yamamoto’s storyboards are filled with this kind of unique directorial guidance (?).

(T/N: The “(?)”s are part of the text of the comments.)

Footnotes

[1] A Brazilian architect known for designs that make the most of curved lines. ↩

[2] David Lynch is an American filmmaker known for his incredibly surreal works. David Cronenberg is a Canadian director known for his particular brand of body horror. ↩

[3] Edward Yang is famous Taiwanese filmmaker who passed away in 2007. Along with the 1986 film, Terrorizers, A Brighter Summer Day is a representative work of his. ↩

Thank y’all for this! Here’s the full storyboard for the first episode:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/y7la8rwhh7yqe9b/Michiko%20%26%20Hatchin%20%2301%20Storyboard.pdf?dl=0

LikeLike

Oh wow, thank you so much! I’m gonna need to sit down and watch this again, with the storyboard in hand!

LikeLiked by 1 person