Images of Gen Urobuchi from natalie, Shōji Kawamori and Hiroyuki Yoshino from Animage Original vol. 1, and Mari Okada from CUT No. 285.

Your pledges help support articles like this! Consider supporting WMC with as little as a dollar today!

In conjunction with megax‘s current series of posts on anime pre-production, which I was privileged to get a preview of a few months back, it’s time for one of the first posts that came to my mind when I embarked on my exploration of ‘Anime Writing’. Be it in reviews, forum discussions, or even on twitter, wherever anime fans gather, you’re sure to hear praise and criticism of ‘the writing’. But what are exactly are we talking about, and who is responsible for it?

To help answer that question, I’ll be expanding on megax’s post on “Scripting” this week, looking in detail at how an episode script for the typical anime is produced. As you might expect, the main writer–aka the series composer–is always a part of this process. But from producers to directors and assistants, there are typically many others involved. And contrary to what most fans seem to assume, the main writer is not the one in charge.

What does an anime script look like?

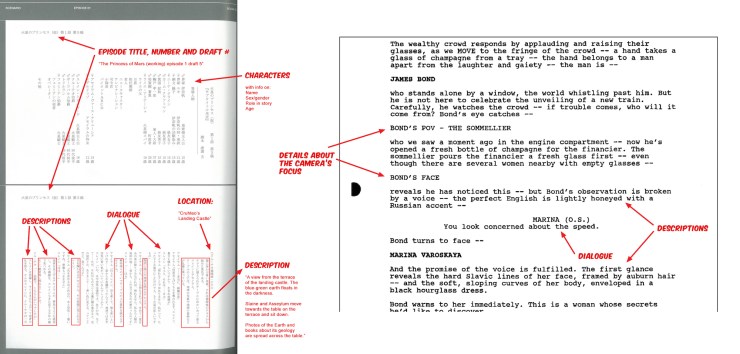

Let’s start by finding out what a script actually consists of. Like key animation frames and background image boards, scripts are a part of the production process that most viewers rarely see. There are actually two different scripts made for each episode, the episode script and the recording script. Today, we will look at just the former.

The episode script, known as a “scenario” (shinario / シナリオ), is a document that a screenwriter produces. The term comes from an Italian word that meant “a sketch of the plot of a play” when it entered the English language in the 19th century. When Henry Kotani introduced “scenario” to the nascent Japanese filmmaking industry during the 1920s, it referred to a document that “consisted of a list of scenes that described the silent action and camera angles.” The use of the term in the two languages has since diverged; today, English speakers typically use it to refer to “an outline of the plot.” In Japanese, “shinario” can also be used to mean something like “an outline,” but in the film, TV and animation industries, it will mean screenplay or “episode script” most of the time.

These episode scripts are quite similar to the screenplays that you’d find in the Western TV and film industries, but with several key differences. First, they list the characters appearing in each episode at the start of the document, with a short description of who they are the first time they appear in the series. Second, anime screenwriters do not describe what the camera is doing in their scripts—they specify locations and describe what the characters are doing, but specific details such as the length of a shot and the way it is framed are left to the staff that storyboard and animate each scene or cut.

Back to the beginning: from story to script

However, the scripting process is quite similar to what you’d find in the West. As megax outlined last week, the overall plot of a show is typically decided during the planning stage and included in the production proposal. For Aldnoah.Zero, Gen Urobuchi wrote a plot outline of two to three sentences per episode, following lengthy discussions with director Ei Aoki.[1] In the case of Yuri!!! on ICE, Sayo Yamamoto decided early on what the results of the Grand Prix Final would be, and worked backwards to set out which episodes would cover the various training and competition arcs. She then partnered with Mitsurou Kubo to outline the development that the characters would undergo in each episode.[2] The writing team will also try to ensure that each arc and the story as a whole has a coherent and well-paced narrative. This part of the process corresponds to what Avatar co-creator Mike di Martino has called “breaking the story”.

However, the handfull of sentences in the plot outline need to be expanded upon further before a writer can turn it into an entire episode script. As shown in SHIROBAKO, a number of people can be involved in this process. Besides the director, the series composer (and the screenwriter for that episode, if applicable), you may also find producers, writing assistants, and perhaps one or two other staff at these “script meetings” (hon-uchi / 本打ち). Once the room agrees on the broad outline for an episode, which should also contain a coherent and well-paced narrative, the screenwriter assigned to that episode will write the first draft of the script. This normally takes one to three weeks, then the same staff gathers again to discuss the draft and provide feedback that the writer will use to revise the script. This process is repeated until the room agrees on a finalized draft—usually the fourth or fifth one. As far as I can tell, the process in most anime writers’ rooms isn’t quite as formalized as in the Western TV industry; I’d recommend having a look at the premise, outline and scripting stages of The Legend of Korra for a comparison.

This piece has focused on originals so far, but for the most part, a similar process occurs with adaptations. First, the main writing team (usually producer, director, series composer and publisher representative (or occasionally, the original author)) decides which parts of the original the adaptation will cover. This is often restricted by the number of episodes that have been greenlit. Having been given just one cour for Wandering Son, director (Ei) Aoki eventually came to the conclusion that covering the protagonists’ middle school years, with the climax being Shuuichi going to school in a girl’s uniform, would be the best idea.[3] But once again, exceptions may exist. In the case of Erased, director Tomohiko Ito made the decision early on to keep the anime to one cour, so as to maintain a strong feeling of suspense. megax goes into a few more examples in his post this week, so do have a look there as well. Next, the series composer will divide the story across the episodes, again keeping narrative and pacing in mind. The rest of the scripting process is pretty much as outlined above, except that the writer will have the original text as a reference.

Another interesting point to consider is how scripts are assigned to different screenwriters. This isn’t always necessary—Jukki Hanada (Sound! Euphonium etc), for example, prefers to be the sole writer on a show, so as not to waste the effort that others have put in. But most projects will involve multiple screenwriters, both as key members from the planning stage or as pinch hitters that take on only one or two scripts. In such cases, the series composer will often assign episodes according to each individual’s strengths. This is why Shigeru Murakoshi worked on the Knights of Sidonia episodes with many “family drama” scenes, whilst Tetsuya Yamada is credited for many of the battle episodes.[4] Psycho-Pass featured yet another division of roles, with novelist Makoto Fukami writing the initial drafts that were then reworked by Urobuchi (both were also involved from the planning stage).[5] Finally, besides their own scripts, the series composer is also responsible for keeping each writer on task, and for keeping track of any plot changes that will affect other episodes. Their role is basically to support the director as the head of the writing team.

If you’d like to know why Okada is such a popular choice for series composer, noitaminA producer Kōji Yamamoto gives one answer to this question here.

Every situation is different

Do note, however, that it’s impossible to know exactly who is involved in each part of the writing process unless one of the core staff members discusses it in an interview or ‘making of’ special. Having a large production committee does not necessarily mean lots of people are always in the writers’ room trying to steer the ship—for Yuri!!! on ICE, for instance, Yamamoto and Kubo were pretty much left to their own devices during the initial writing process. This is reflected in the opening credits, where the two of them are credited for the story (原案).[6] On the other hand, when working on Macross Frontier, series composer Hiroyuki Yoshino enjoyed putting together ideas pitched not only by Shoji Kawamori and (series director) Yasuhito Kikuchi, but also by the producers from Satellite, Big West and Victor Entertainment. Similarly, many different individuals contributed to the story of Aldnoah.Zero, and they are all credited for “original work” (原作) under “Olympus Knights.”

It also does not mean that everyone in the room will contribute equally, or that the same person will have the exact same role in a new work in a franchise. For example, Yoshino noted that Shiro Sasaki, the producer representing Victor Entertainment, was “all about the music” during the Frontier script meetings. Line producers, who are responsible for staffing and allocating resources, will typically try to ensure that action sequences are spread out across the episodes. Massive redrafts late in the scripting process are thus one of their worst nightmares. In the case of Psycho-Pass, although Urobuchi was one of the main writers for the first series as well as the movie, his role during the script meetings for the second series was largely to provide feedback on the ideas that everyone else brought to the table. In short, every situation is different and we have to consider them differently.

The episode script is done. Now what?

Once the episode’s script is approved, the individual screenwriter’s work on the episode ends, and the script is set for the next stage of the production process: storyboarding. But the writing process does not actually end here. I will be back at some point to cover how the script continues to evolve through the rest of the production process. If you’ve found this post illuminative and helpful for understanding ‘anime writing’, then I hope you will join me again then.

Footnotes

[1] Roundtable featuring Aoki, Aniplex producer Atsuhiro Iwakami and producer Shizuka Kurosaki from the Aldnoah.Zero EXTRA DAY event pamphlet.↩

[2] Aldnoah.Zero actually started with Iwakami, who felt that Aoki and Urobuchi would be able to create an interesting mecha series together (much like Iwakami felt a magical girl show from Akiyuki Shinbo would be interesting (Madoka Magica)). Urobuchi would later leave the project in order to work on Kamen Rider Gaim, but the plot outline that he came up with remained largely intact, with a few minor changes. You can read more about it here. For Yuri!!!, although Yamamoto drove the project, it was TV Asahi who made the original request for “a sport series.” And that’s why the story is centered around the Grand Prix Series—TV Asahi has broadcast rights for this competition, whilst Fuji TV has the rights for the other major competitions and many ice shows in Japan.↩

[3] Interview in CUT No. 285, June 2011. Going by this interview on the noitaminA website, Series Composer Mari Okada may have already been involved in the project by this point (late 2009). However, Aoki specifically notes that “starting from the beginning…just didn’t work for me” and that it was after reading this particular development in the manga that the anime crystallised for him.↩

[4] Episode commentary for Knights of Sidonia episode 5, with Series Composer Sadayuki Murai and Polygon Pictures Producer Hideki Moriya (MC: Hisanori Yoshida) ↩

[5] Urobuchi’s interview in SF Magazine August 2014 (Vol.55 No.701). The project began with Katsuyuki Motohiro and Naoyoshi Shiotani, who invited Urobuchi to join them about 1-2 years in. ↩

[6] In the Go Yuri Go fanbook, Yamamoto mentions that a number of people tried to get the two of them to change the scene at the end of episode 7, but does not say at what stage and in what form those requests were made. However, the ending to the show (the results of the GPF and what happens to the characters afterward) was all set in place right from the planning stage.↩

Thanks so much for the in-depth detail! I’m doing a presentation on the anime production process and this has helped me a lot when it comes to understanding anime episode script writing.

LikeLike

You’re very welcome — glad you found it useful! (And feel free to reach out to me on twitter if you have any other questions — there is a second half, but unfortunately, it hasn’t been published yet ^^;)

LikeLike