The following interview was originally published in the Digimon Movie Book (2001). Translated by Twitter user @NohAcro. © 2017 Wave Motion Cannon

The following interview was originally published in the Digimon Movie Book (2001). Translated by Twitter user @NohAcro. © 2017 Wave Motion Cannon

Hey, it costs money to post translations like these! Any amount helps, even ¥300!

(Continued from Part 1)

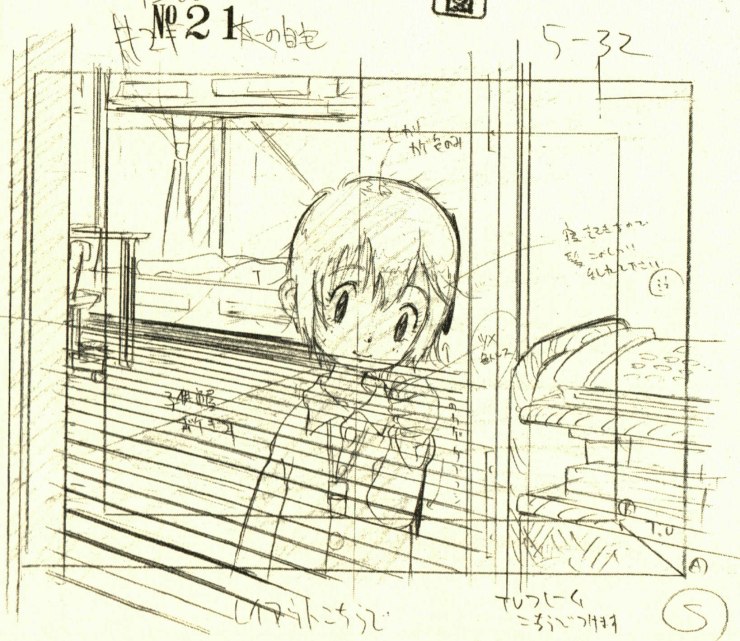

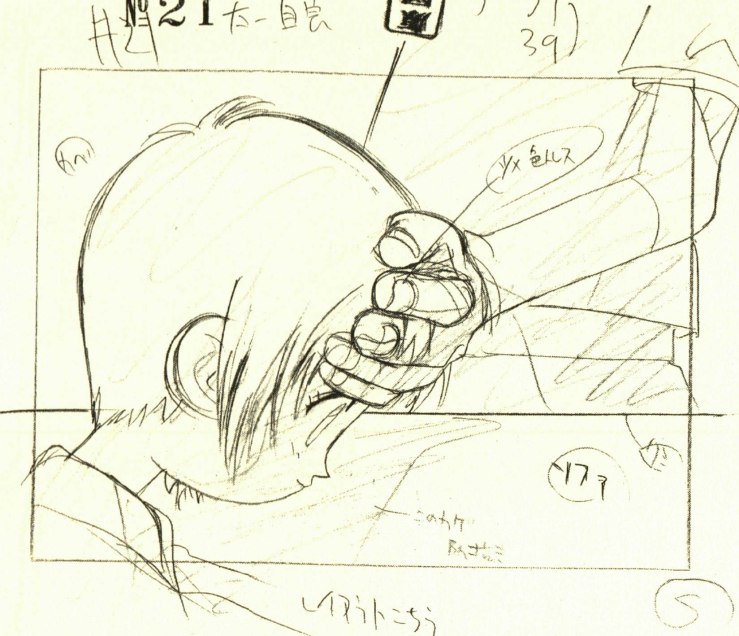

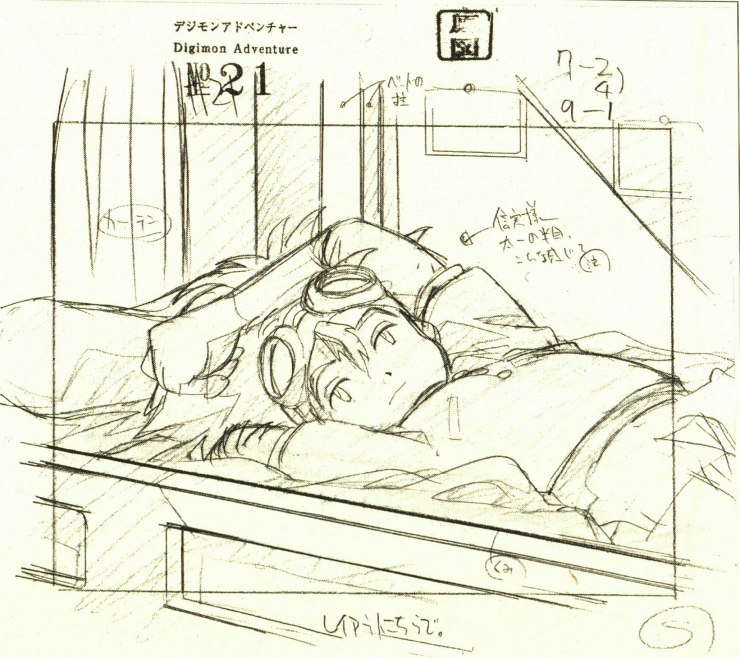

The truth behind episode 21 of the TV series…

Moving from the films, we would like to ask you about episode 21 of the TV series you directed. The setting is a little bit different from the films, isn’t it?

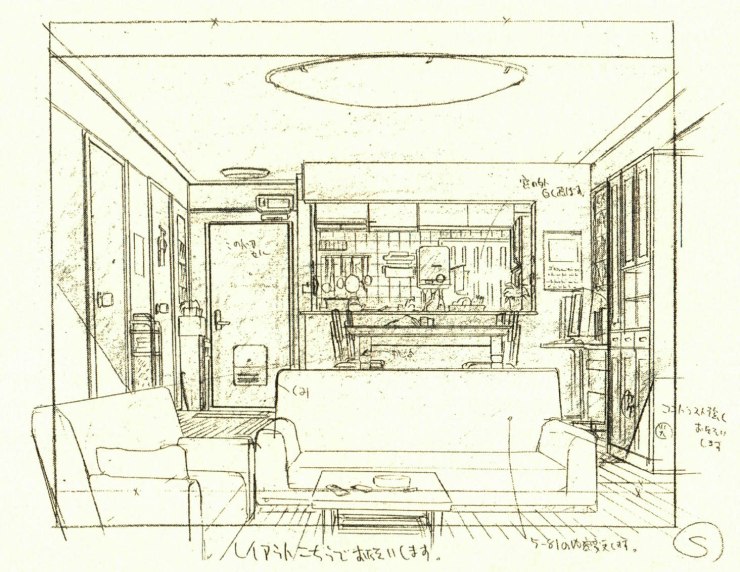

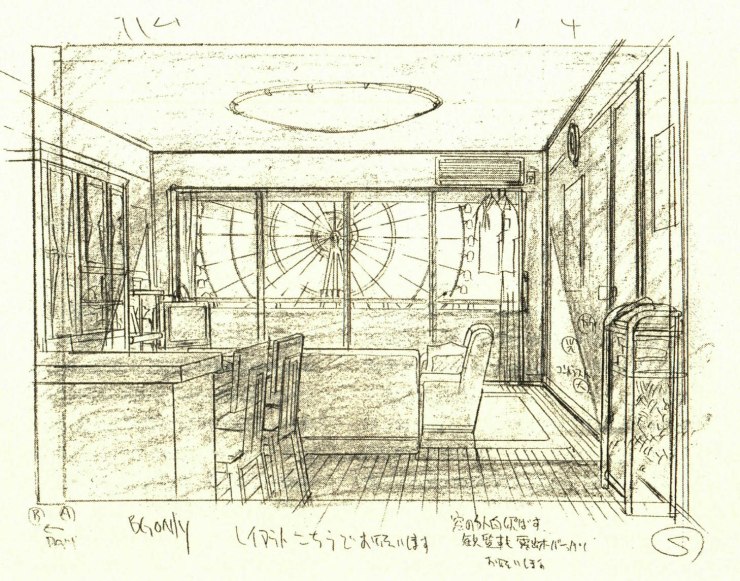

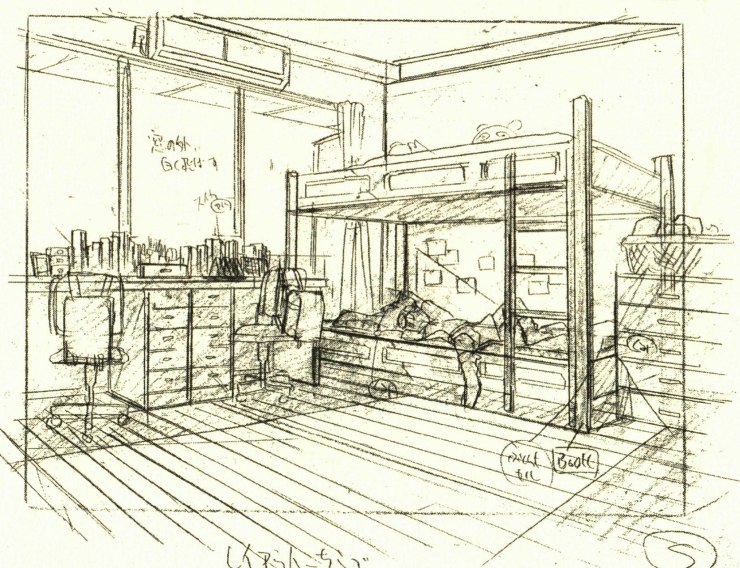

Yeah, quite a bit (laugh). I could even go as far as to say that episode 21 is completely different from all the other episodes. Besides, the Ferris wheel we see outside the window is a mirage (laugh). I put it there only because I needed an oppressing landscape, but I was told that the settings that would be made for this episode would also serve for future ones, but if they did that, that Ferris wheel would be completely out of place. That’s why I followed the modified settings from the show in the second film. Well… episode 21 is Taichi’s dream after all (laugh). In a way, this episode is like peeking at an intercourse from the outside, in the middle of the afternoon. You can either see it as a story about a beautiful love between siblings, or something that goes even further, with a somewhat erotic feeling to it.

That’s why Hikari looks more mature, with an ennui feel.

There was weirdly erotic atmosphere in the episode (laugh). I remember someone telling me “That episode smelled.” When Hikari was clinging to Taichi, they’d say “She’s clearly not just caring for her brother”…that kind of thing an adult can see. Children would only look at it and say “Yeah, she’s a really caring little sister.”

It’s almost surrealist when they talk about the time he covered her when she wetted the bed. Not only the dialogue, but the pauses are so atypical.

Kae Araki-san really understood the intent behind the direction, she wasn’t playing the role as a simple little sister (laugh). We could even go as far as to say that the episode is a love triangle between Koromon, Hikari, and Taichi.

We have Taichi, lying on the sofa in a languorous summer sunlight.

He was acting as a proper hero until then, but once he comes back home, he starts thinking about home sweet home, his summer homework, that kind of stuff. There is a fight between Taichi who’s an elementary schooler in his daily life and Taichi who’s a hero in the Digital World.

There’s that, and Hikari’s conflict as well.

If you ask me what her conflict is about, I think it’s a battle between her and Koromon. There’s a scene where Taichi’s just lying on the sofa, and Hikari and Koromon are eating watermelon next to him. But she’s not having a single bite of the watermelon. That pretty much is a conversation about the husband between his wife and his mistress, like “Please leave him. You can eat that watermelon all you want but please give me my husband back.” (laugh)

When you look at her eyes at that moment, you know she means something…

She’s not just a cute little sister, she senses that her brother is in danger, and tries to bring him back. And she’s not straightforward in doing this, she’s using all the female appeal of a second grader to win him on her side. If we had to use a parable, Hikari would be the wife past her 30’s, and Koromon would be an innocent 20-year-old girl (laugh). She’s still young, but she cannot remain indifferent to the fact that her husband just got chatted up by a younger chick. I would imagine her saying stuff like “You may get along in the Digital World, but I’ve been with him for 8 years since I was born.” or “I know everything about you two, don’t think you can hide it from me.” It’s that kind of messed up relationship.

(laugh)

And by doing so, even the summer element starts to feel ominous. It’s all humid and hot, and humans’ true faces emerge from it.

Maybe that explains the lazy atmosphere. By the way, how does the episode connect to the first film? Taichi doesn’t have any memory of those events, does he?

He doesn’t, and the episode underlines it. That’s why he’s bewildered when Koromon appears in the first episode. I think it’s like a dream for him, which he’s reminded of 4 years later, during his fifth grade. Yet Hikari remembered it, and she could see the Digimon. That’s why she calls him out on it, saying she knows everything. She doesn’t have special powers or anything like that, she’s driving him into a corner by exposing what she knows, what a bewitching girl (laugh).

I want to resist antagonism of Good vs. Evil as much as possible.

Your directing is characterized by how often you put two elements in contrast in order to emphasize them. In the climax of the second film, we could cite the moment when Diablomon is stabbed, and the sound effect is substituted with the microwave’s timer, or in the first film where we can see that among two lifts in the apartment complex, one is broken. Whether it’s for the story or picture, we often find that kind of structure.

I’m doing that on purpose. What I often do is, I don’t just depict something I really want to show in details, but I’d rather put something totally different on the side, to create that emotion when something you thought was normal turns out not to be. That includes technical points in directing, of course, but what I really want to avoid is creating a dichotomy between allies and enemies based on different characters’ viewpoints. That kind of impression can vary even in relationships between people, and asking someone what kind of person they are won’t necessarily give you a better answer either. That’s a distinction I didn’t do in the first film, and I didn’t want to.

Even if we consider our reality, we cannot represent it as an antagonism between two clans.

Right, that’s why I think it’s difficult. In the old days, people believed that if we could get out of poverty, everyone would be happy. It was as simple as “Poor = Bad” and “Wealthy = Good”, or the opposite. But in the end, no one can know which side was actually happier. I think the reason why we try to make a dichotomy is because we want to find the right answer. People want to interpret the world as a law, which would allow them to set a goal and be relieved. But nowadays, it’s becoming an increasingly common perception that good and evil aren’t absolute, but just relative values.

Reality doesn’t come with a clear answer, does it?

In that case, as a storyteller, we either have to take a “so-what” attitude and designate who is evil anyways, or create a story where we do not clearly know who is who. I did the latter to make the first film, and the first to make the second, while still letting ambiguity upon the righteousness of both sides.

The Net Digimon in the second film appears more as “something dangerous” than evil.

Right, since the Net Digimon is more like some kind of bug, it’s closer to a natural catastrophe in that sense. That’s why we cannot consider it as a straight up evil, and Taichi doesn’t have any hatred toward Diablomon. He just wants to avoid a threat. The generation before us have grown only with stories about moral justice, so they cannot help but look for an antagonist, but that’s their problem (laugh). And I think people of the next generation are aware of the fact that they don’t live in that kind of world anymore. It’s not worth holding a grudge against the world, instead it’s more important to think about realistic ways to deal with it. What Taichi does in the film is pretty much that… or maybe that’s a bit of a stretch. I think that’s the reason why there is a sense of “contrast” within me. Even at a point where the world has just been saved, some people regret that they failed at baking their cake. It’s not about Taichi’s mother being unaware, but rather her looking at a whole other world. In the first film, Taichi and Hikari don’t see Digimon the same way, so the fact that adults cannot see them is not about them not having the right for it. It’s just a whole other part of the world, and some people don’t see them. That’s what I wanted to explain to children. They aren’t happier than adults because they can see Digimon, in fact there is no antagonism. Or maybe there is, but no one said that one was better than the other.

It is a difference of viewpoint that comes from individuals, or different steps in maturity.

Right, that’s why in the second film, among chosen children, there was a divide between those who fought and those who didn’t. I thought it would seem more likely for the audience… or should I say that they would get the feeling that this is what happens in reality. This is what we call “the World.” I wanted to show that. Once you have a group of 8 people, that group needs an ideology.

To keep the group together.

Exactly. And it would often end up being something like “Saving the World”. Well, at least it’s easy to understand, but that’s something I want to resist to… which is another ideology in some way (laugh). Even so, I want to resist to an ideology which divides things in good and evil.

My goal is to depict unrealistic things in a realistic way.

There are several cooking scenes throughout the second Digimon film.

There’s a quite technical reason for that. I wanted to give the audience a sense of daily life, that the world onscreen is connected to our world. This is particularly important in animation. It might seem odd, but scenes where people are just eating are not particularly important in live action since you instantly get the feeling that you’re looking at a living human being. But animation is drawings, so convincing the audience that the character is alive becomes an important part of the work. That feeling can even be gratifying. This is something you cannot get from a live film. That’s why I think dining scenes in live films and in animation bear a fundamentally different meaning.

You mean it is a device to enhance the characters’ presence?

Right, but I don’t speak for all animation…I even think animation has different specificities from live film. In animation, you can directly conceptualize characters or ideologies and communicate them to the audience, and things that you don’t need won’t appear onscreen as long as you don’t draw them. So we could go as far as to depict a character who doesn’t eat or go to the bathroom. You can create a character purely out of concept. Animation offers that possibility.

But animation nowadays leans towards realism, doesn’t it?

Yeah, as if realism was somehow superior (laugh), or higher-quality. But you need to ask: what does realistic mean? For example, some people would say that it’s realistic to see a Windows OS screen, but is that really the case? Because you know, it’s a drawing (laugh). I think the fundamental reason why people seek realism is because reality itself doesn’t feel real, despite the fact that it’s the world they’re living in. Or sometimes animation feels more real to them. And I guess it’s because reality is actually absurd. Considering that, I think it’s even more meaningful to ask what the meaning of depicting “realism” is. I think realism as an unaware display of technique or a pursuit of details is meaningless.

Despite all that, there are lots of actual locations or objects in these two films. What is the motivation behind that?

The reason I represented Hikarigaoka or Odaiba as they are in reality wasn’t to represent those places realistically. What I really wanted to represent realistically was Digimon, and things like human feelings.

Things that are not tangible?

Right. In short I wanted to depict unrealistic things in a realistic way, and the fact that apartment complexes or Odaiba feel realistic is just a tool for that. The other reason is objectivity. If I set it in an imaginary world, it would likely imply a subjectivity from the creator, and I wanted to avoid that. But I think the biggest reason was really to depict things that are not considered as realistic in a realistic way.

So by setting the action in a place with a shared image, you could emphasize abstract concepts?

I guess. So that’s also contrasting. By putting unreal Digimon in contrast with a realistic Hikarigaoka apartment complex, I wanted to make Digimon feel real in that environment. And as I said just before, I think Digimon are quite like human feelings. I don’t seek realism on the visual aspect, but on feelings the audience can empathize with. Even if they see a character that’s just concept, there are moments when they can feel that their actions are a continuation of what they do in real life… I seek that kind of realism. And that’s something you cannot get by simply improving the animation quality. On the contrary, it’s even more interesting in animation when you can find that continuity despite the world being completely different from ours. I think representation really is about giving a shape to things that don’t have any.

I draw storyboards like I make music, caring about rhythm.

Now I would like to ask you about your works other than Digimon. First about the amazing episode 14 of Himitsu no Akko-chan … The way the film turns into music… particularly the first 3 minutes.

That part until we get to the subtitle contains one fifth of all 300 cuts in the episode, so that’s 60 cuts (laugh). The reason behind it is because Seki-san loved creating original songs. So during the scenario meeting, we were writing the song in parallel.

Was the song made only for that episode?

Yes. At first we wanted to ask Yasuharu Konishi-san from Pizzicato Five for the song (laugh). We even sent him a proper offer, but he couldn’t for scheduling reasons. At first glance, Chikako seems like an ill-mannered girl from downtown, but we wanted to show a cuter side of hers, so the song is a little bit classy as well.

I thought it was a little different from a straightforward musical, it was more like the film itself becoming music.

To make it so, we had to have the music first. Furthermore, that song had to correspond to what we asked for, and we needed to base our storyboards on it to make the episode work. That’s why we were really tight on schedule. But the fact that it was episode 14 played a big part. If it were a later episode, we would have had to include songs from previous ones too. That episode was made possible because the director was able to command a song based on the script’s image.

Is that sense of speed characteristic of your directing as well?

I guess so. I tend to draw storyboards like I make music. I think a lot about structure. In TV anime I worked on, there are lots of same-position –when you use the same drawing repeatedly-. The reason for that is first cost performance, and also the fact that repetition itself can create a tempo or a rhythm. Actually in terms of cost performance, same-position doesn’t make a significant difference, and from animation staff’s point of view, it’s even better not to use it. So the reason I use it nonetheless is for rhythm and tempo. On the other hand, if you use same-position without managing to create that rhythm, it just looks cheap. That’s why you need to think about combination and the way you align sequences.

I cannot stand serious tension, I always feel the need to put a punchline somewhere.

Do you like comedy?

I love it, I would like to do only that (laugh).

There are some wacky scenes in the second film, like when Taichi looks at the screen and Miko makes the exact same movement.

That kind of humor works because of the nonsense in the middle of sense, having that silly detail in a serious scene. The second film has more moments like this. Since film 1 was so serious, the second ended up with a strong “Look, silly people are moving left and right” feeling.

It is more comedic.

It is a comedy, as opposed to the first one.

Kitarou episode 113 has a very Drifters* feel to it.

Yeah, The Drifters (laugh). Like “Shimura! Look back!”.

The moment when the Gotoku-neko tries to get out of Nurarihyon’s mansion, the way it reacts to sudden sounds really reminded me of The Drifter’s “adventurers” sketch.

It’s a classic among classics by now, which strangely isn’t done that much in animation. Not only this but classic gags in general, whether it’s Drifters or the ones of Yoshimoto Shinkigeki don’t appear in animation very often.

It’s a typical trick that has been done for decades in comedy. Their comedy is based on movement.

Right, they depict silly people in a silly way. But you don’t see really silly characters in animation nowadays, everyone’s becoming so serious. That’s why when I’m doing a comedy, I want to do something stupid really seriously, or something serious in a silly way. I cannot help but messing it up when I’m doing serious stuff.

You want to intervene as the creator, pointing out something in the situation (laugh).

That’s exactly it. Humor needs objectivity, you cannot do comedy in a subjective way. The audience has to be in absolute control of the situation. If you get too attached to a character, you cannot make a gag out of them anymore, since the situation becomes subjective. You know, there are situations where someone stupid is trying very hard to do something, they are very serious about it, but also very funny from an objective point of view. If you give too much importance to that character’s viewpoint, the situation becomes subjective, what they do feels more serious, so they could do the silliest things on earth, it wouldn’t be funny at all. And gags in animation often tend to fall into that category. You need to have an objective point of view to make silly people look silly, but most anime and films are shot subjectively, so they don’t work as gags in that sense.

Gags is really about the process of a third party laughing at the suffering of someone else, despite the situation being tragic for the one implied.

Right, the more the situation is unfunny for those who suffer from it, the funnier it is for others. The reason I like comedy is not because I like making people laugh but because I like objectivity.

Both of us are right in the middle of The Drifters and Hyokin-zoku generation, right?

Yeah, if I remember how it went, in our generation there was first The Drifters, then Kin-chan, and after 1980 we got Hyokin-zoku. From there we got a shift in mentalities, where gags became mostly about parody.

It was the same case for Tunnels or Ut-chan Nan-chan.

Right. That’s why there are a lot of parodies in sketches on variety shows. Parody in itself is a form of objectivity, but that forces the audience to know the original material, so it narrows the spectrum of gags and comedy in general. Now if you ask yourself what non-parodic or classic comedy were, I think it consisted of parodying human beings themselves, not a certain work.

People are a lot of fun when you look at them objectively.

Indeed…like, they have hairs in some strange places when you think about it (laugh).

So you like comedy with that aspect?

Yeah, but like I said it’s not that I like to make people laugh. I just personally have a hard time dealing with serious situations, I can’t help but mess with them. It doesn’t need to be specifically funny… it’s almost a visceral thing. I get tired if I keep making a serious face (laugh). Well, there are two sides to the problem. The first 30 minutes of the second film were made from a rather silly viewpoint, so I thought I could make the transformation scene at the end a little bit more serious. If it were serious from the beginning, it may have ended with something super funny popping out from under the cape (laugh).

You instinctively try to end it with a punchline?

Exactly, the scene at end when the missile hits the river and people on the shore just fall down is symptomatic, I couldn’t do otherwise. When I’m directing, that kind of thing will always happen. I basically lack seriousness (laugh).

*The Drifters are a Japanese band and comedy group, most famous for their variety show “It’s 8 O’Clock! Everybody Gather ‘Round” which aired from 1969 to 1985.

(Continued from Part 1)

Special thanks to @NAveryW for sending us the interview scans, and @Josh_Dunham for providing the storyboard drawings.

Gracias.

LikeLike