**When the word Lain is italicized, I am referring to the anime series, and when it is not, I am referring to the character Lain Iwakura.

In 2012, ANN produced two Best of the 90s podcasts, and, appropriately, two of the panelists put forward Serial Experiments Lain as one of the decade’s best anime. However, some disagree on the grounds that Lain’s vision of the future, specifically its depiction of the purpose and mechanics of the internet, does not turn out to be accurate. The implication is that Lain hangs everything on what prove to be false prophecies and is therefore outmoded as a work of fiction.

This series of essays will attempt to refute the notion that the show doesn’t offer anything to the modern viewer. I will be writing one article structured around the thematic content of each episode. I’m not interested in the stuff that Lain’s first-time viewer doesn’t know, stuff like the mystery of Lain’s identity. Nor am I interested in how the show’s technology maps to our world today. The show’s detractors are perfectly correct: it really doesn’t. Yet, while it is true that certain aspects of Lain’s prophetic vision don’t come to pass, perhaps the fundamental presuppositions about human nature which serve as a foundation for this vision are also true? To put it another way: even if the particular facts of the future Lain predicts are wrong, the broader messages of the series still speak to universal human experiences.

What I am deeply interested in is the philosophical/theological core of Lain, as well as its imagery. I believe that these are where the series reveals itself to still be tremendously relevant and valuable. But, who knows, maybe I’m wrong? Maybe there isn’t the value in the show that I think there is. I’m rewatching the show for the first time in a long time; maybe I’ll finally see how wrong I have been. Still, I want to believe! You’ll come along for the ride that is this grand experiment, won’t you?

Great! Let’s get to it then.

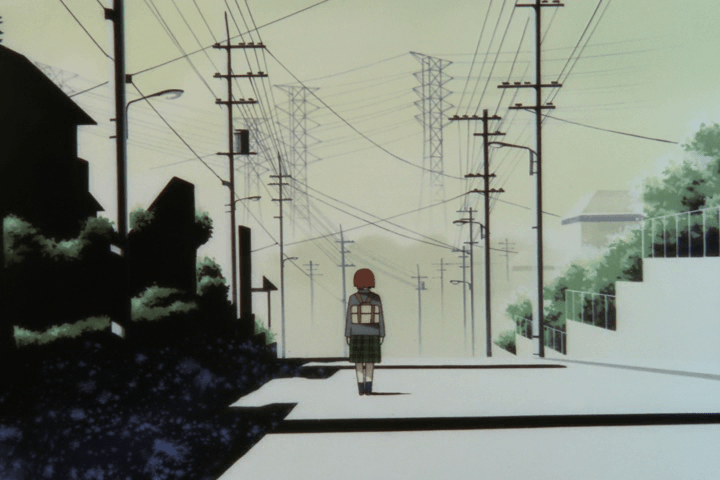

Lain Iwakura is alone. The anime’s first episode makes this fact painfully clear. Whether she is by herself in her room, on a crowded subway car or in class surrounded by familiar faces, Lain seems to exist in isolation. Ironically, the place she seems most alone is her own home. Episode one gives us a vertical slice of her home life, beginning with a family meal. Silence hangs heavy over the dinner table, and afterwards Lain unsuccessfully attempts to reach out to her parents. She tries to talk to her mother about a classmate who committed suicide, but her mother outright ignores her. Later, Lain asks her father (who skipped dinner) for a new computer, and, though he verbally responds to his daughter, he never once looks at her or emotionally engages with her. Instead, Mr. Iwakura’s eyes and heart remain fixed on his computer monitors.

Where there should be one connected family unit, four isolated beings dwell within the Iwakura residence. Connection is a core concept in this series, and episode one expertly conveys that raw ache we feel when our attempted connection fails. The unsettling scenes of Lain’s home life do a lot of heavy lifting here, but, interestingly, the episode also explores the notion that maybe something is “off” even when people want to connect with each other. At school, Lain observes one girl attempting to comfort her crying classmate. Though the girl being comforted does not stop crying, this act seems to be an authentic sort of connection between friends. Yet, Lain is utterly unmoved by it. We see her turn around in her desk to take in the scene, and the camera pans over her eyes. Instantly, we’re aware that Lain sees no meaning in what’s taking place. It’s almost as if she is looking to be impressed and just absolutely isn’t. Something about that connection does not feel right to Lain. It doesn’t seem as “pure” and authentic as it should be. So, what exactly is the problem?

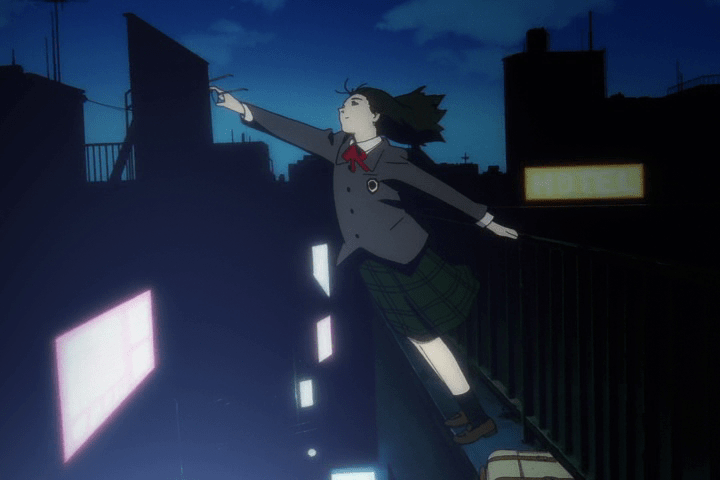

Here, we should consider the role of Lain’s classmate, Chisa. Her brief part in this episode is brutal and indelible. In Lain’s first scene, Chisa takes her own life by willingly letting herself fall from the roof of a building. The shot of her loosely holding onto a rail with one hand while leaning over the building’s edge, without a hint of fear, is burned into my brain. It’s one of the most iconic images in a show filled with iconic images. Chisa seems to be reaching out for something, someone, with one hand as the fingers of her other hand slowly slide off of the final physical object she would hold onto. And then she falls to her death.

Chisa wants to leave behind the physical world and somehow exist as a consciousness in the digital one. The audience is prepped for this by the anonymous messages that appear from time to time throughout the episode. An early one reads, “If you stay in a place like this, you might not be able to connect.” Remaining in the physical world prevents true connection, and Chisa herself alludes to this belief. In an email exchange with Lain, taking place days after Chisa’s suicide, the later claims that she killed herself because God is in the digital realm.

Whether Chisa means that the Being called God lives there or that her newfound lack of constraints meets a spiritual, existential need, it is all the same in this respect: interpersonal communication is different in The Wired (a term some characters use to refer to the internet). Both interpretations of her statement imply that obstacles to connection, with God and with others, that exist in the physical world are not present in the digital reality. Clearly, Chisa doesn’t regret the choice to take her own life. The chatty tone of her emails suggest that she feels much more at home, much more herself than she did before. She is now able to connect. For Chisa, this digital connection is more authentic than the other kind. It’s ironic that Chisa’s final act in the physical world–the act that allows her to establish true digital connection in the first place–breaks up a potential sexual connection, the sort of connection some see as the pinnacle of communion in the physical world.

Lain is very receptive to Chisa’s message. It provides an appealing explanation for Lain’s feelings toward the physical connection between her classmates. The emptiness she feels is not reflective of herself but of the inauthentic nature of the connection. Chisa’s beliefs are also reinforced by Lain’s family life. At home, her father remains eerily spellbound by online interaction, while attempts to connect with her mother or sister fail miserably. Perhaps it isn’t always like that. Mrs. Iwakura could be feeling sick, or Lain’s sister could just be in a bad mood. We are given a small sample to extrapolate from, after all. However, even if things aren’t always so bad, that only strengthens Chisa’s argument. In her reality, there is only the communication. Sickness, stress, irritations, hunger, lust, tiredness…none of those physical barriers impede connection in The Wired.

Still, this message may be hard to swallow. Everyday sensory experience tells us that our physical world just is our reality. Something is “more real” if it happens physically than if it happens in one’s mind. We might say the former “actually happened” while the latter did not, looking at no other factors than that one act occurred in the physical world and the other did not. Yet, Serial Experiments Lain puts forward the notion that there is something that is “less real” when it occurs in the physical world than the digital world: interpersonal connection. More precisely, the experience of connection is more pure in the digital world due to the lack of traditional, physical obstacles to its success.

Consider the following (rather haunting) imagery. During a particularly dull moment of school, Lain’s attention begins to wane. Her vision blurs in and out of focus, and the noisy snap of the chalk on the board sounds farther and farther away. She puts down her pencil and looks at her upturned right palm, her hard stare almost willing change to occur. Thick streams of mist suddenly pour out of her fingertips and lazily swirl about the classroom. No one else seems to notice. Though, reality for Lain has become what we might call distorted, it is also quite actual to her. Yet, since neither the teacher nor the other students perceive the phenomenon, most would argue that it wasn’t “actually happening.”

This scene highlights an important distinction. When people talk about a thing being real, they aren’t actually talking about the bare fact that it exists in the physical world; rather, they are referring to the fact that we agree that it exists in the physical world. Thus, if we follow the theory, the foundation of reality lies not in the existence of things but in a sort of tacit handshake between human beings. This shift introduces all sorts of variables (e.g. the reliability of perception) that, at the very least, make the concept of reality less straightforward.

And this, I think, is the upshot of the first episode. Under scrutiny, the concept of reality proves to be less straightforward than everyday sensation would have us believe. Lain wants us to consider the possibility that what is most real isn’t the ground that we agree is under our feet but a particular kind of experience. If that’s true, then shouldn’t we drop what we’re doing and seek it out? Shouldn’t we return to The Wired?

I loved this essay, but I would posit that Lain’s view of technology proved to be far more accurate than what you have heard being said seems to give it credit for. The Knights of Eastern Calculus for what little we actually see of them seem to be very similar in many regards to Anonymous, to a degree that is incredibly impressive on the part of Lain’s staff. They’re this mysterious group of web vigilantes that really seems to just be made up of a bunch of random individuals claiming the moniker, with little, if any, kind of centralized command structure. I can’t even think of any predictions about technology that were incorrect. Certain things, such as the construction of Lain’s computer and the nature of The Wired from a coding/mechanical standpoint, were certainly over-the-top in a surreal manner, but in my mind those were clearly abstractions created to establish an atmosphere or advance a theme, and not meant to be visions of the future. As your focus on the topic suggests, it is Lain’s ideas about humanity’s interactions with (and via) the internet that were truly prophetic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shin-chan, I couldn’t agree more. Like I alluded to in the post, I think it matters very little that Lain’s future technology is schematically or materially similar to our own. The crucial thing, the thing that allows us to keep coming back and mining interesting stuff from the series, is that at a conceptual level the show grasps the breadth and scope of then-future-now-present tech and, also crucially, how people interact with it. And, yes, later on in the show the OTT nature of Lain’s rig would seem to be a thematic device.

Oh man, I forgot about the Knights. It’s been a few years since I’ve seen the show, so I’m looking forward to take that stuff in with a fresh perspective.

LikeLike

Great essay! Lain is very much relevant today. We’re more digitally connected than ever, but we’re physically growing further and further apart. It probably won’t be long before the worlds start to blur.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not long ago, I thought that the cyberpunk fiction of the last 20-30 years was pure fantasyland stuff. I’m beginning to think that we might be headed in that direction, in more ways than we are able to realize now. I don’t think we’ve reached the top of the hill on the roller coaster, but I am curious (and anxious) to see if there is some single event or series of events that turns out to be the thing that pushes us over the hump and sends us barreling toward that future.

LikeLike

What you called mist was actually intended to be ectoplasm. Most people think it’s smoke. I’ve never encountered a fan who has correctly identified it, including myself. (But you did describe the scene as haunting, so maybe you’ve come the closest.) I only know because I read about it from Chiaki Konaka’s scenario book. It also says in a footnote that Takahiro Kishida, who did the layout for all of episode 1, spent an entire month-and-a-half on the layout for that scene alone. It sounds like a long time, but maybe he was multi-tasking… he had a lot of jobs in SEL, including character design, key animation, and animation direction. The title of the music track during that scene is also “Ectoplasm,” so there’s one clue that I suppose someone could have used to deduced the true nature of the smoke.

It’s interesting that you went into the reliability of perception, because the ectoplasm scene is an extreme example of an epidemic in fan analyses of SEL. People often fail to figure out what’s actually happening on screen. I’m not even talking about subtext or meaning or philosophy, just the actual events. For example, there’s a post on a blog I won’t name where the blogger says Lain was telling the people on the train to shut up. And there’s an entire forum thread somewhere (I can’t find it at the moment) in which multiple people seem to believe that Alice had sex with the teacher in episode 8. The ectoplasm doesn’t really matter, but those things do.

Anyway, it was nice to find some Lain on here. I hope you’ll continue the series. It’s difficult and been done a lot, but I still don’t think it’s been done enough.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the helpful information. I do plan on continuing the posts at some point, so don’t lose hope!

LikeLike