Few in the anime industry are as committed to their own artistic enterprise as Masaaki Yuasa. A director who’s slowly risen to prominence over the last 15 years, he’s established himself as one of the foremost creative minds in anime today. He has the reputation of a fastidious and ambitious auteur, with a talent for wringing the best out of his animators. His internationally-informed sense of design defies nearly every stereotype about the Japanese style yet has managed to avoid falling into its own form of mannerism. And most importantly, his work displays a genuine zeal for the wide compass of human experience. With Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki retired, Mamoru Oshii stuck in live action, Satoshi Kon dead, and younger TV-centric creators like Hiroyuki Imaishi and Kenji Nakamura struggling to relive the glory of their first few shows, Yuasa is arguably the only working anime director of truly global merit.

Though most anime fans are probably aware of his work as a director, his career as animator isn’t as well documented. Masaaki Yuasa started out at the relatively obscure contract studio Ajia-do, sister studio to Shin Ei of Doraemon and Crayon Shin-chan fame. Ajia-do’s founders Tsutomu Shibayama and Osamu Kobayashi, the legendary animators behind such A Pro gag comedies as Tensai Bakabon and Dokonjo Gaeru, were an early inspiration for Yuasa and it was in working on Ajia-do’s and Nippon Animation’s Chibi Maruko-chan that he cut his teeth as an animator. Shortly after Maruko-chan he joined the team of Crayon Shin-chan and under the supervision of director Mitsuru Hongo he began to refine his skills as an artist. Shin-chan opened many doors; most significantly, he served as animation director for Hamaji’s Resurrection, Shinya Ohira’s infamous episode of The Hakkenden. By the end of the 90s Yuasa was a rising star and since then, first with short films like Noiseman Sound Insect, Slime Adventures, the Vampiyan Kids pilot, and later with larger projects such as Cat Soup and Mind Game, he’s made a name for himself as one of the most original voices in Japanese animation.

However Yuasa’s time as an animator at Ajia-do and Shin Ei is still relatively unknown, particularly among English-speaking fans. As such I reached out to Mr. Yuasa over Twitter and organized a set of interview questions based around this period of his career (with translation thanks to Twitter user @SeHNNG, who is a regular contributor to Altair & Vega). His answers are below. I hope to make interviews of this sort a regular feature at Wave Motion Cannon, but Yuasa’s uncommon generosity may set the bar too high for future subjects.

*******

First of all I’d like to thank you immensely for taking the time to engage with someone on the other side of the globe like this. Most of your fans overseas are probably aware of your accomplished career as a director with Mind Game, The Tatami Galaxy, Cat Soup, and such, but few know about your past as an animator at Ajia-do and Shin-Ei, which is what I wanted to focus on in these questions.

Ajia-do was the very first studio you worked for. Looking back, was it run any differently compared to other studios you’ve worked at since? Is there anything the anime industry could learn from a small outfit like them?

Ajia-do was a studio formed by a number of very skilled animators who also knew how to handle all the other directorial processes. Its philosophy went something like “don’t just be good enough to do, get good enough to do it.” As a result of that—and the huge amount of work I was given—I learned an enormous amount.

After my four years there, I’d worked as a key animator, in-betweener, layouts, storyboarder, character designer, setting planner, animation director, and director. Doing key animation under Shibayama and other top animators there was a huge help. I’m a fan of the system they used in Ajia-do for in-betweens: they’d always have the key animators check the second drafts. I’ve worked at a lot of studios since Ajia-do, but I still think quite fondly of them.

Elsewhere you’ve talked about your love for the A Pro shows animated by Osamu Kobayashi and Tsutomu Shibayama. What was it like working with anime legends like them? Did they ever coach the younger animators?

I only very rarely worked directly with them, but the few times I did, they shocked me with their incredible work ethic and erudition. And to add to that, Shibayama-san was an enormously flexible and progressive individual. Thinking back on it, I bet that they actually wanted us to approach them with questions, but I was too nervous to do so. There was a time when Shibayama-san visited me after I became a key animator. I’ve learned so much from him, and I still treasure the conversations we had.

One of your earliest projects at the studio, Ahoy There, Little Polar Bear, looks nothing like what one would expect from you. It looks closer to Yasuhiro Nakura’s or Manabu Ohashi’s work than Shin-chan. Is there a reason why you haven’t revisited this style?

Polar Bear began as a picture book, and I wanted to reproduce the book’s aesthetic. The line work had to strike the right balance of tension and shakiness. It was nerve-wracking work; sometimes it made me want to get out of my chair and scream. I think I would’ve gone nuts had I continued to work like that.

There’s a massive jump between your earliest work on things like Polar Bear and Anime Rakugokan, and your animation for Chibi Maruko-chan. What caused this shift?

I believed that styles should change to match the material, and I was taught that the mark of a skilled animator is the ability to change their style on the fly. When I was younger, I wanted to experiment with as many modes as I could.

Actually, for the Chibi Maruko-chan television series, Tsutomu Shibayama devised this sort of planar aesthetic to match the manga’s style.

Rakugokan was an original creation, so we had more freedom with it. I loved A-Pro’s style, but I felt that it wasn’t what I was looking for with Rakugokan. When I left Ajia-do, I thought I would stop trying to imitate A-Pro’s style—I ended up incorporating it into my style anyways.

So much anime from the 80s and 90s focused on realism but your animation shows little trace of that. Were you deliberately reacting against that trend?

When I began, I wanted to experiment with tons of styles, and realism was one of the things I wanted to tinker with. But a lot of the realism of the time wasn’t quite what I had in mind, and I wanted to focus on a form of realism that matched my style. Let’s talk about Hakkenden. The director, Ohira-shi, is one of those masters capable of not only rendering beautifully realistic drawings, but also of imbuing animation with a sense of freedom. His style struck a chord with me, but I wasn’t skilled enough to actually pull it off, and it would’ve been deeply inefficient on my end to try. Along with Ohira, there were a number of animators who could draw at a far higher level than I could

Is there anything peculiar about your approach to animating? Your scenes stand out dramatically and are immediately recognizable, with an approach to color that’s unlike anything in the industry.

I try not to just go through the motions. I think drawings, music, colors, backgrounds, and voice work are attempts to express certain things; that’s become my motivation. So when I use photographs, I take special care not to reproduce the drawing so much as express what I see in it.

Your scenes in Chibi Maruko-chan: My Favorite Song reminded me of Yellow Submarine. In general, your animation shows more influence from non-Japanese sources than is usually the case with anime. Would you say there’s a bias in the anime industry against Western cartooning like Warner Brothers and MGM? How would you describe your relationship to foreign animation?

While Japanese animators were of course a huge influence on me, I can’t deny that there was a freshness to foreign animation. I didn’t care where it was made, so long as it was novel. I think there are plenty of folk in the Japanese animation industry who adore Warner Bros, but I just feel like there’s very little demand in Japan for the kind of work Warner Bros does.

You joined Crayon Shin-chan in 1992 and became Mitsuru Hongo’s righthand man on the movies shortly thereafter. Did moving from Maruko-chan to Shin-chan change your day-to-day routine much?

Hongo-san and I worked together at Ajia-do, so there wasn’t much of a generational gap between us.

I had a lot of fun with Crayon Shin-chan—the characters’ designs are very simple, and we had access to all of the animation paper we could ever want. I worked non-stop, believing that I would never again have the opportunity to work on something as fun as Crayon Shin-chan. Thanks to Hongo-san’s guidance and the success of the products, I started gaining a lot of attention. And above all, Crayon Shin-chan gave me regular experience with storyboarding. I’m indebted to Hongo-san for being so flexible and giving me the opportunity. Through setting and storyboard work, I experienced a complete 180 in how I thought about animation. It wasn’t just this grueling process; I genuinely enjoyed and loved what I was doing.

You were set designer for the first few Shin-chan movies. What exactly did this entail? Were you producing exploratory sketches for the the storyboard and backgrounds? Did you do layouts?

It involved cataloging buildings and sceneries for later reference, planning out interior decoration and props, designing cars and vehicles, and thinking up ideas for action. And I developed this natural ability to generate setting and plot ideas, though those ideas weren’t exactly the most well thought-out. I don’t recall using too many of my ideas, though.

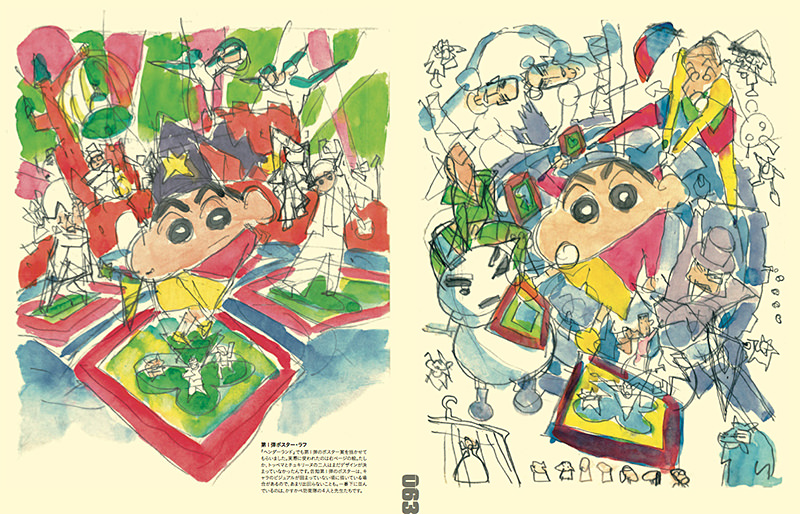

Your work on the Shin-chan movies seems to homage Miyazaki’s parts in the later Toei Doga films. The theme park in Crayon Shin-chan Movie 4: Adventure in Henderland is a direct reference to the tower in Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves, right?

Hongo-san was a huge fan of what Toei was creating at the time, and I think that love of Toei bled into the styles we used in our films. Of course, we’re far below Miyazaki-san’s level, but his influence is undeniable. We set our eyes on simple designs like the ones used for Puss in Boots or Animal Treasure Island.

We designed Henderland with those two movies, Disneyland, and a slew of other theme parks in mind. I used to watch Miyazaki-san’s scenes in Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves over and over again, I loved them so much. So there has to be some of him in Henderland.

Did working on Shin-chan in this capacity influence you to go into directing or were you always intent on being a director? In this respect was Miyazaki an inspiration?

Initially, I was only interested in drawing; in fact, I didn’t care much for directing at all. But because of all the work I did on Shin-chan—designs, ways to express action, tons of reference books—I kept running into new fields, and these translated into new interests and ideas. And, of course, storyboarding was huge for me. It seemed to me that charting everything out, planning out the drama and action, and really capturing the soul of my characters expanded my horizons as an animator. And it was several times more interesting than anything I’d done before.

I felt I had reached the end of my progress as an animator, whereas directorial work seemed to me like an endless expanse to reclaim.

Going back to animation, Masami Otsuka was one of the major figures behind Shin-chan but not much is known about him. Do you have any particular anecdotes? What motivated him to push the Shin-chan designs in such an extreme direction?

I thought about Otsuka-san a lot. He’d produced so much great work.

There was this saying, actually: “All the Otsukas are amazing.” Meaning Masami Otsuka, Shinji Otsuka, and Yasuo Otsuka.

I remember one of the senior character designers for Ajia-do’s Fuku-chan telling me how much Otsuka-san influenced him. He was the quiet type, so we didn’t really have too many chances to talk. What shocked me most was when I first saw his work as a key animator on Esper Mami: I remember thinking that it didn’t really look that great. But when I saw the scenes in the television broadcast, in motion, they amazed me. That made me realize that key frames didn’t need to be drawn all pretty. I also began using action recorders around that time, after seeing how he’d preview his cuts with them. Before that, I’d mostly adhered to the mainstream idea that action recorders weren’t that useful, as time spent using those could be used drawing instead.

Speaking of Shin-chan animators, Yuichiro Sueyoshi was obviously a kindred spirit. How did you meet him? Would you say you influenced his peculiar style in any way?

I met Sueyoshi-san while working on Shin-chan, at Ninpen Manmaru. He’s a refreshing, good-humored person.

Sueyoshi-san’s work on Crayon Shin-chan: Pursuit of the Balls of Darkness—specifically the return to Tokyo scene—left a deep impression on me. Actually, at the beginning, we had so many of the same drawing habits that a lot of people had trouble distinguishing between my drawings and Sueyoshi-san’s. It’s funny: he told me that his work changed because he loved the way I drew. But even though I spent most of my time sitting down at a desk and drawing and Sueyoshi-san played around and spent half his time taking breaks, he still produced far more drawings than I did and much more skillfully than I could. I’m no match for him.

On Shin-chan you often animated scenes of characters running in a goofy fashion. Do these types of scenes have a special appeal for you?

I believe running is an immediately parseable action that conveys a lot about characters’ emotions.

While working on Shin-chan you were animation director for Hamaji’s Resurrection, Ohira-san’s famous episode of The Hakkenden. How were you able to land such a pivotal assignment?

I actually didn’t even know Ohira-kun at the time. But I believe he saw some of my work on Crayon Shin-chan and then reached out to me.

I’ve noticed that after working with Ohira-san your animation started to use more and more rounded forms, whereas earlier scenes in Maruko-chan are more angular. Would you say there’s a tension between “soft” and “hard” figures in your designs?

I’d worked with rounded forms in my art before; I think I learned a number of different things from Ohira-kun. I’ve always been influenced by the people around me, but I think Ohira-kun’s had an especially large influence on me. For a while, I wanted to emulate his realistic, dynamic style, but that didn’t work out.

But I found myself wanting to work simultaneously with gekiga-esque and cartoonish styles. Every time I drew something in a ‘harder’ [“gekiga-esque”] style, I wanted to jump right back into the soft, and vice-versa. So there was a tension in that I wanted to work both styles simultaneously.

After The Hakkenden, you started working on projects all over the industry: Studio 4C, Production IG, JC Staff, even Ghibli. Was this a dramatic change for you?

Thanks to my work on Crayon Shin-chan, I had offers for work flowing in. I worked at other places between the Shin-chan movies.

Every studio has its own way of going about things. At the beginning, having only really worked at Shin-ei and Ajia-do, working at these new places with people I’d never met before seemed very foreign. But as I picked up things here and there and began working with others, my style began changing bit by bit. It was pretty big when digital production began catching on, too. Once you get used to all the adapting you have to do, you come to realize that each of these studios have their own merits.

Do you ever miss being an animator and not having to worry about direction? Are the Ajia-do days at all nostalgic for you?

I’m always looking forward to the next project, so sometimes it’s easy to forget about the past. The early days of my career, while tough, gave me incredible learning experiences.

Do you have any other comments or anecdotes related to what I’ve asked about? Maybe a funny story about a famous animator?

I’d just like to mention and thank my former colleagues at Ajia-do, Hiroyuki Nishimura, Masaya Fujimori, and Takayuki Hamana, for the immense influence they had on me.

And for all the fans out there, any hints at you’re working on right now? If you want to stay discrete I understand.

We’re working on a film based on a novel and two original films for the family audience. Depending on how things go, comics aren’t out of the question.

Thank you again for taking the time to respond.

In terms of Yuasa’s work, I’ve really only seen The Tatami Galaxy and Ping Pong, but both made a big enough impression on me that I consider him one of my favorite directors. It’s fantastic he was willing to do this interview and I loved learning a bit about his time as an animator.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This was extremely awesome and exactly the kind of content I hope to see more of here. Thanks so much!

Yuasa will always be one of my favorite directors. His unabashed passion for artistic expression at the expense of marketability has led to some truly fascinating projects. 3 potential films, huh? I’m down. I hope the one that’s not for family audiences skews more toward Kemonozume or something. Man, I would kill for more of that Yuasa.

You guys should try to get an interview like this with Ohira-san now. 😛

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yuasa is so nice~

Iso-san interview pls (=゚ω゚)ノ

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for this. Yuasa is my favourite director!

LikeLike